A., an early crossword-puzzle fan, often called public attention to these errors in his famous column “The Conning Tower.”) Miss Petherbridge proved so good at preventing errors that she soon became the unofficial crossword-puzzle editor, and was even permitted to try her hand at making puzzles. One of Miss Petherbridge’s duties was to see that the puzzles appeared without typographical errors, which had long been a vexation to readers.

Farrar, then Miss Petherbridge, and newly graduated from Smith, got a job as secretary to John O’Hara Cosgrave, editor of the magazine section of the Sunday World. The present square shape and pattern of black-and-white squares, as well as the reversed name, were developed before 1920, when Mrs. It scored a mild success, and the puzzle was made a regular feature of the paper. It was shaped like a diamond, had no black squares, contained thirty-two words, and was called a word-cross puzzle. That honor goes to one Arthur Winn, an editor of the old New York Sunday World, in which, on December 21, 1913, the first crossword puzzle appeared. Farrar, who gave us to understand at once that she was not the inventor of the crossword puzzle.

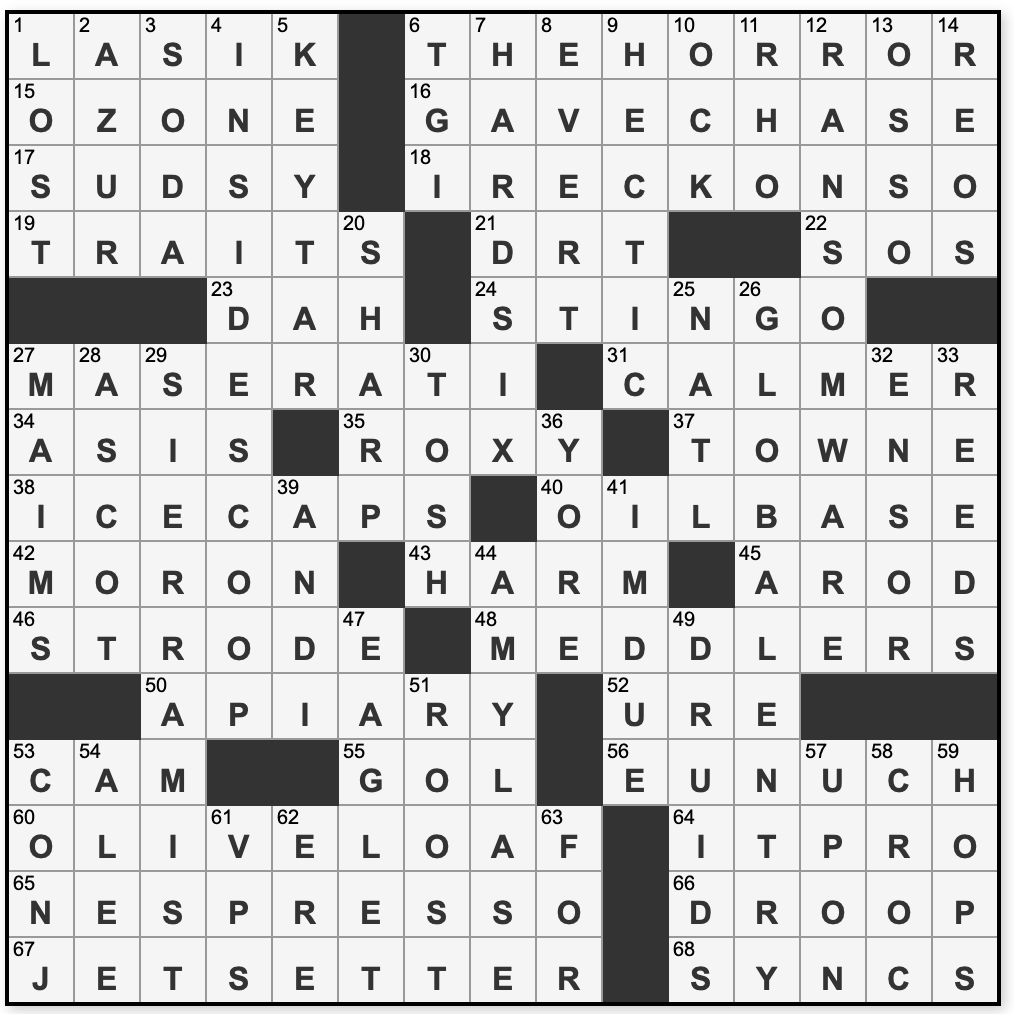

We stopped in at the Times shrine the other day and had a pleasant, reminiscent chat with Mrs. Probably the most important person in the world of the crossword puzzle is a slight, charming sixty-one-year-old woman named Margaret Farrar, who helped launch the craze in her youth and is currently the revered crossword-puzzle editor of the Times. Like mah-jongg, which came along a bit earlier, crossword puzzles might have been expected to suffer a sudden and permanent loss of favor when the force of the craze had spent itself instead, they have endured and prospered, and though they are not much talked about nowadays, they continue to have their millions of ardent addicts. It was exactly thirty-five years ago that the great crossword-puzzle craze began to sweep this country. Margaret Farrar, the first crossword editor for the Times, in 1968.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)